The Making of Brand Brand

Russell Brand has become a lightning rod for criticism, called variously a hypocrite, naïve, self-obsessed and a leech on the system he claims to despise. Here, Third City Partner Mark Lowe talks ‘Brand Brand’

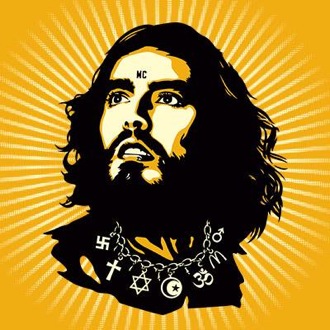

“Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they probably begin by calling “charismatic’,” said one writer of Che Guevara, Russell Brand’s hero. Judging from recent press, he could have been talking about the comedian himself.

A blog ‘on brands’ needn’t concern itself with the rights and wrongs of this, but what is interesting here is that, as Deborah Orr puts it: “By projecting himself as a passionate, radical thinker and anti-establishment poster-boy, Brand is building Brand Brand”.

It’s not entirely clear whether Brand wants to be taken seriously as a political figure, but let’s assume that he does and ask whether Brand Brand has a realistic chance of success.

To do this, it’s helpful to look into the science of political image-making, probably the oldest form of branding known to man. All successful political projects rest on what I’ll call the three I’s.

The first is insight. Much like their commercial equivalents, political brands must identify a consumer need; that is they should tap into a sentiment that is widely held, preferably one that nobody else has addressed. Brand does well here. He’s identified a feeling, particularly among the young, that modern politics is corrupt, venal and irrelevant.

Next, we have image-making; that is, the imagination to build a visual and verbal identity around your brand and the charisma to project this to a wide audience. Brand clearly has an instinct for this, which isn’t surprising for someone in show-business. The irony though is that his profile is super-charged by capitalism. Much like his hero Che, Brand’s longevity as a cultural figure will probably depend on the very economic system he wants to destroy.

Finally, and most importantly, comes the idea. This should be rooted in the insight and set out, without being vague, what you’ll do to address it (aka, policy). The strength of the idea and its ideological consistency are what give political brands longevity. It’s what distinguishes, say, Thatcherism from the Big Society. This is where the Brand-Che comparison breaks down completely.

Like him or not, Guevara lived his political idea, labouring daily to put into practice. Brand, on the other hand, is fixated on insight (diagnosing the problem) and image (how he looks) but has given little or no thought to what his idea actually is. In this sense, he’s learnt everything from Che’s success and nothing from his failure.

Ideas and policy are the third rail of political branding. They take thought and hard graft to get right and more often than not, they fail, as Che discovered. As Christopher Hitchens, the writer I quoted earlier puts it.

“Guevara’s life…(was)…a study in diminishing returns. He drove himself harder and harder, relying more and more on exhortation and example, in order to accomplish less and less.”

Russell Brand, take note.

This piece originally appeared on The Drum